Building Irish Identity

Understanding who we are

Irish Manuscripts dating as far back as the 6th century reveal a self-confident Ireland, a country fully engaged with mainstream European intellectual development, and widely admired. What did our ancestors know? What did they think and why? How did they bring knowledge to the continent?

The answers are found in a unique resource — the manuscripts of the time. Much is known, but so much more remains to be revealed.

Medical Training

The medical manuscripts are essential textbooks derived in large measure from the major medical schools of the continent. They were used by medical families, serving the lords of the time. The learning in these books is typically ‘international and outward looking’, setting the tenets of medical knowledge as understood at the time.

The three main types of therapy, sometimes referred to as ‘the three instruments of medicine’, were diet, medication and surgery.

The second of these, medication, was the principal form of intervention by which the physician treated patients. Most medical recipe ingredients came from plants. The texts contain a vast amount of information about plants and their application.

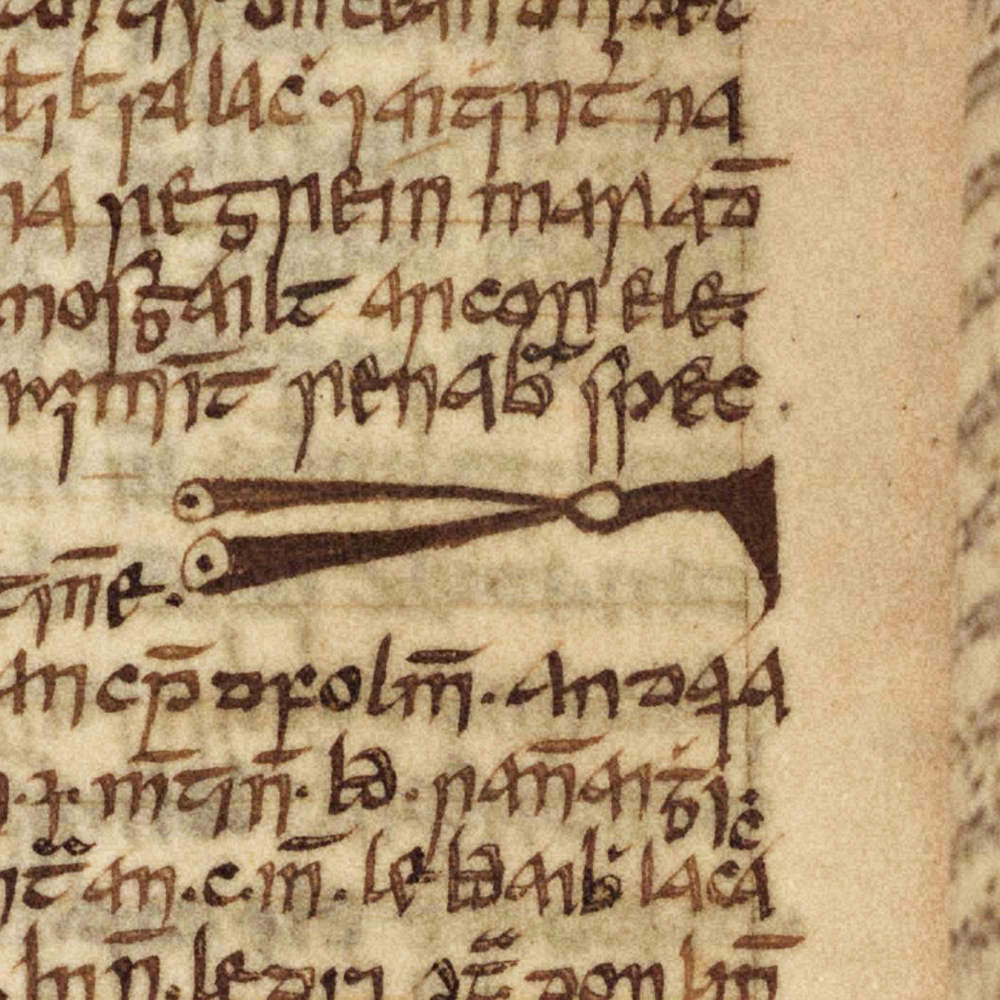

One manuscript contains a diagram of the ‘seven tunics and three humours’ of the eye — its various labels can be identified in modern medical terms.

A further surgical manuscript contains a diagram of a nasal speculum — allowing the inside of the nasal passage to be clearly seen by a physician.

Saga and Myth

The sources of the tales we heard as children

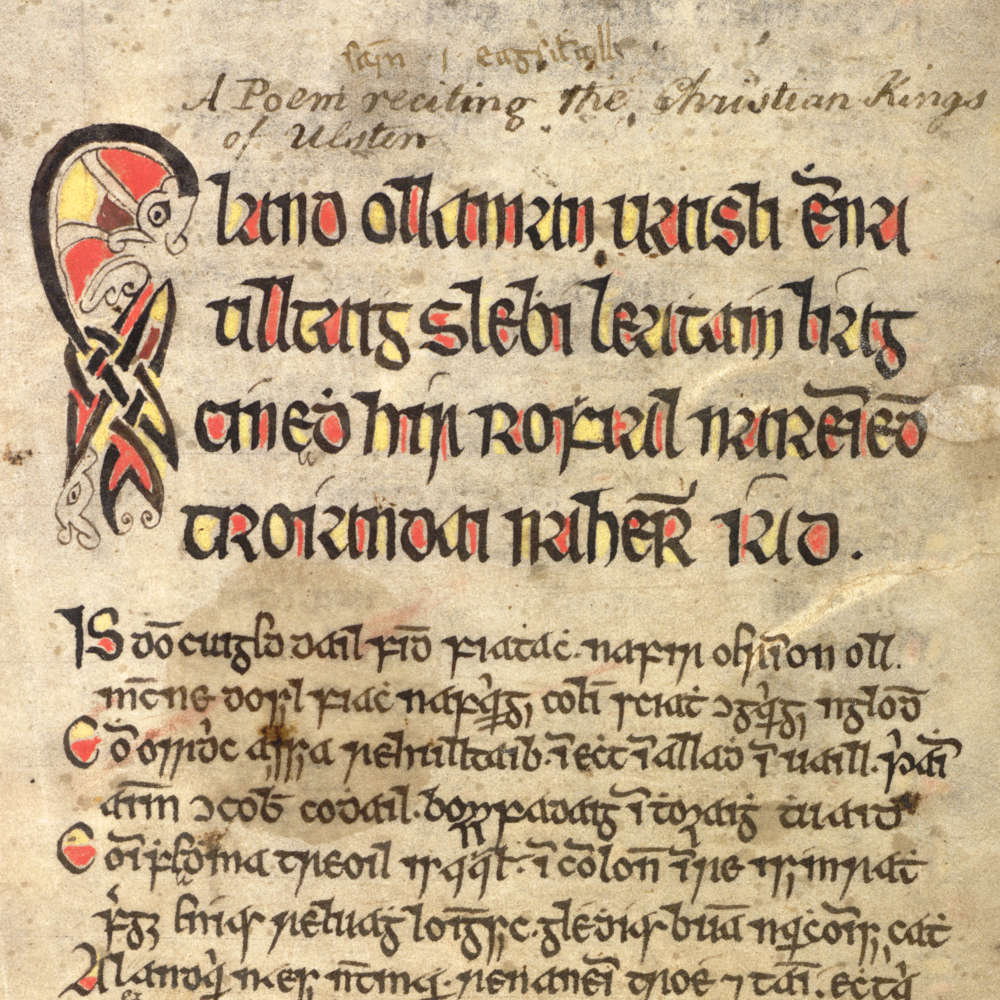

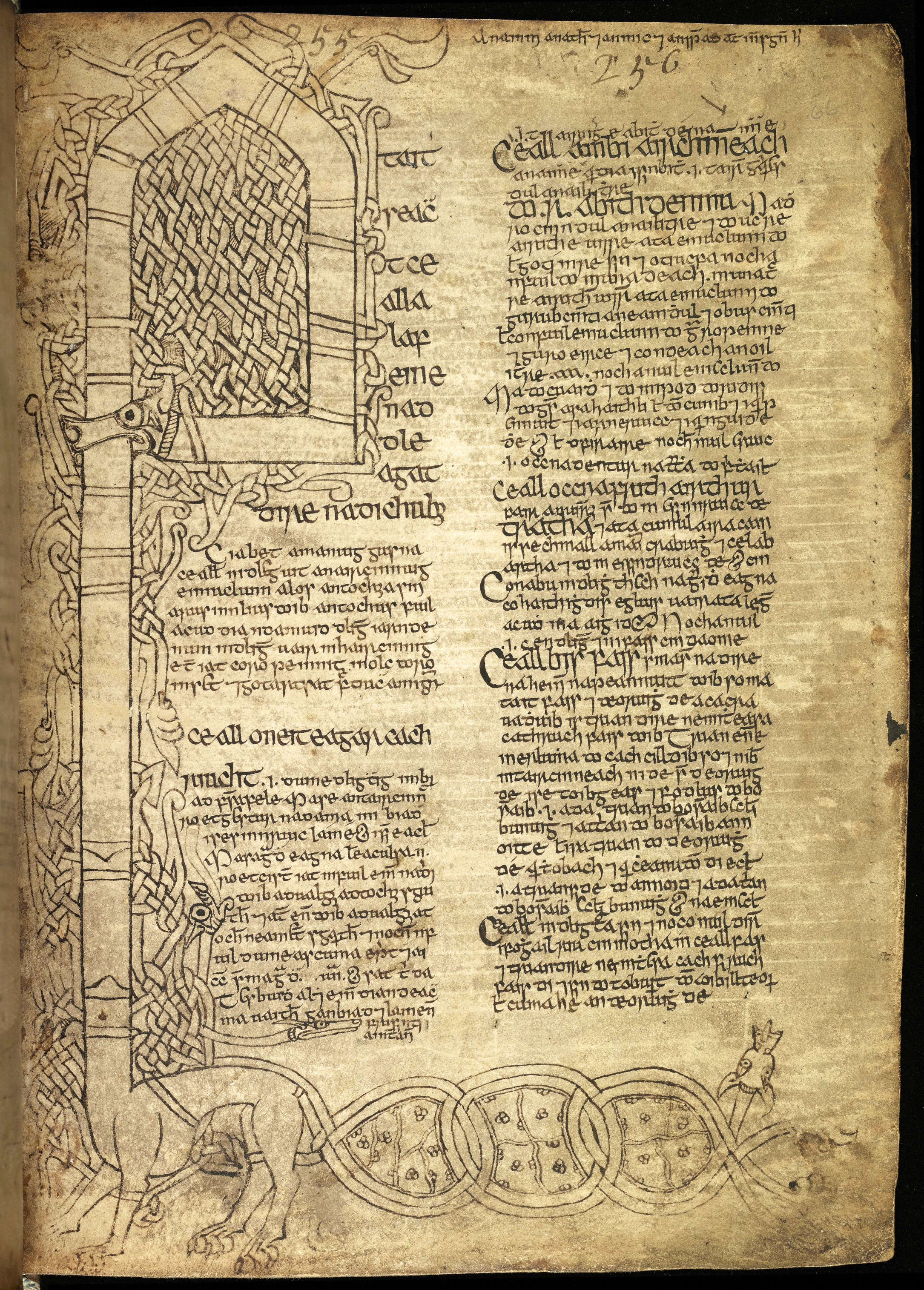

The manuscripts also hold the many medieval Irish tales, poems and sagas that seek to explain the origins of people and places and how the physical and political world of their time came into being. These highly sophisticated compositions display considerable literary and artistic skill. Through tales such as Táin Bó Cuailnge (‘The Cattle-Raid of Cooley’), and Tóraigheacht Dhiarmada agus Ghráinne (‘The Pursuit of Diarmaid and Gráinne’), we encounter the supreme hero Cú Chulainn, the warrior-god Lugh, the otherworldly enchantress Éadaoin, the gifted but doomed Conaire, king of Tara, the wily Fionn mac Cumhaill and many others that inspire and excite the Irish imagination even today. These tales, set in a distant past, in a world in which the supernatural encroached on the lives of mortals, deal with a wide range of human feelings, attributes and experiences: love and loss, loyalty and betrayal, victory and tragedy.

Medieval Ireland Revealed

Religion, History and Genealogy

The Irish — descendants of Noah?

The most influential book in the medieval Christian world was the Bible. The Old Testament traced the origins and histories of many peoples from the time of creation. In their engagement with this fundamental cornerstone of faith and history the medieval Irish encountered a problem: nowhere in the Bible are Ireland or the Irish mentioned. To set this to right and to embed themselves firmly within the scheme of Christian history, Irish scholars set about inventing a legend to explain their own origins.

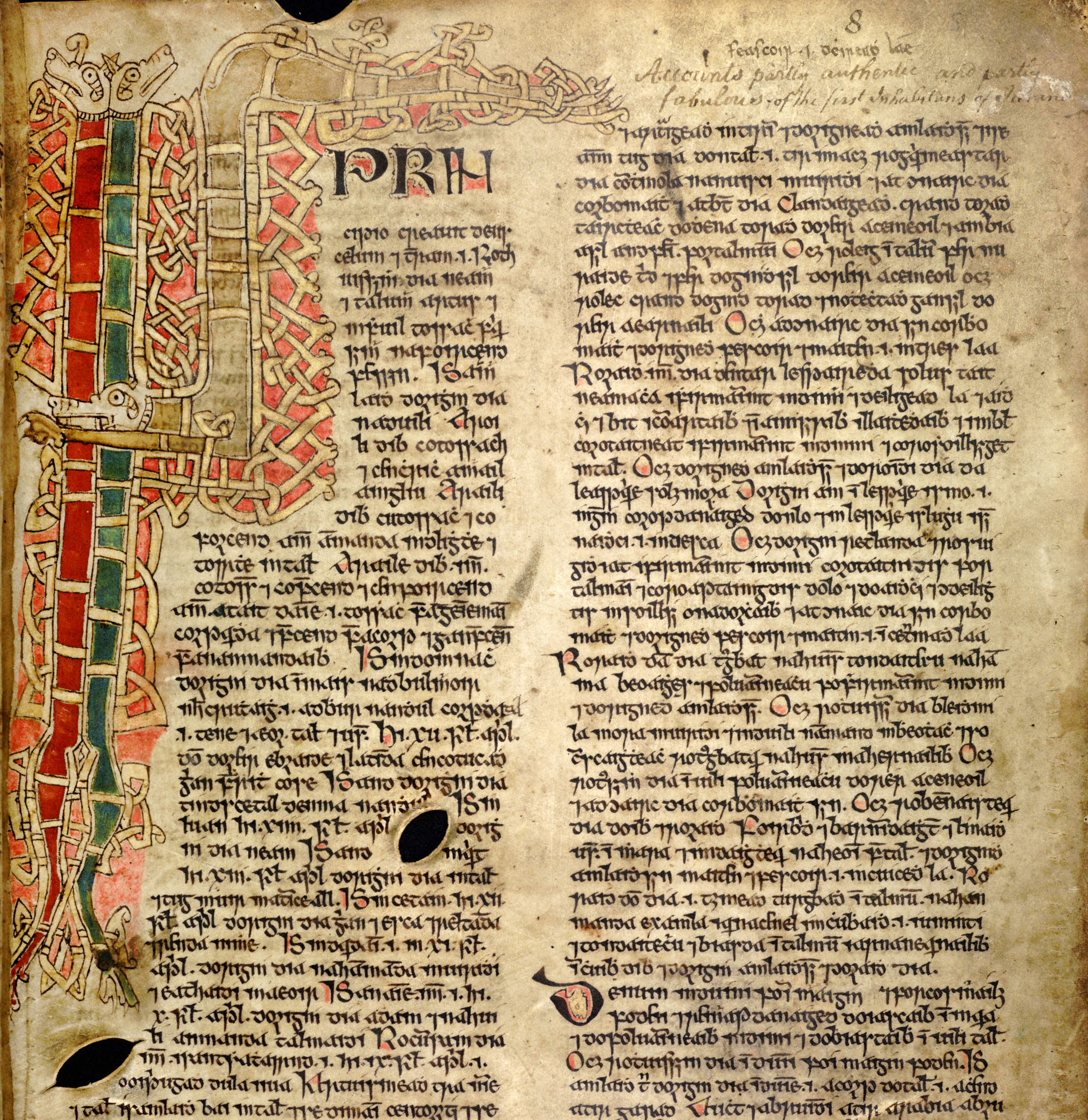

Thus they produced a work we now know as Leabhar Gabhála Éireann commonly called the ‘Book of Invasions’. Here they take as their starting point the great biblical flood that destroyed the world, leaving only Noah and his family as survivors. Claiming ancestry from Noah’s son, Japheth, they wove a narrative that saw his descendants travel in turn to Greece and Spain before arriving in Ireland as the last of a series of invading peoples who laid claim to the land.

Origins and genealogy became immensely important in Irish tradition. Each king and lord, major or minor, had a fixed pedigree that traced his line of descent back over centuries with generations of historical ancestors gradually merging with mythological figures all making their way back to Japheth. Thus assuring their ancestry, pedigree and place within the nations of the world.

Mathematics and Astronomy

Understanding Time

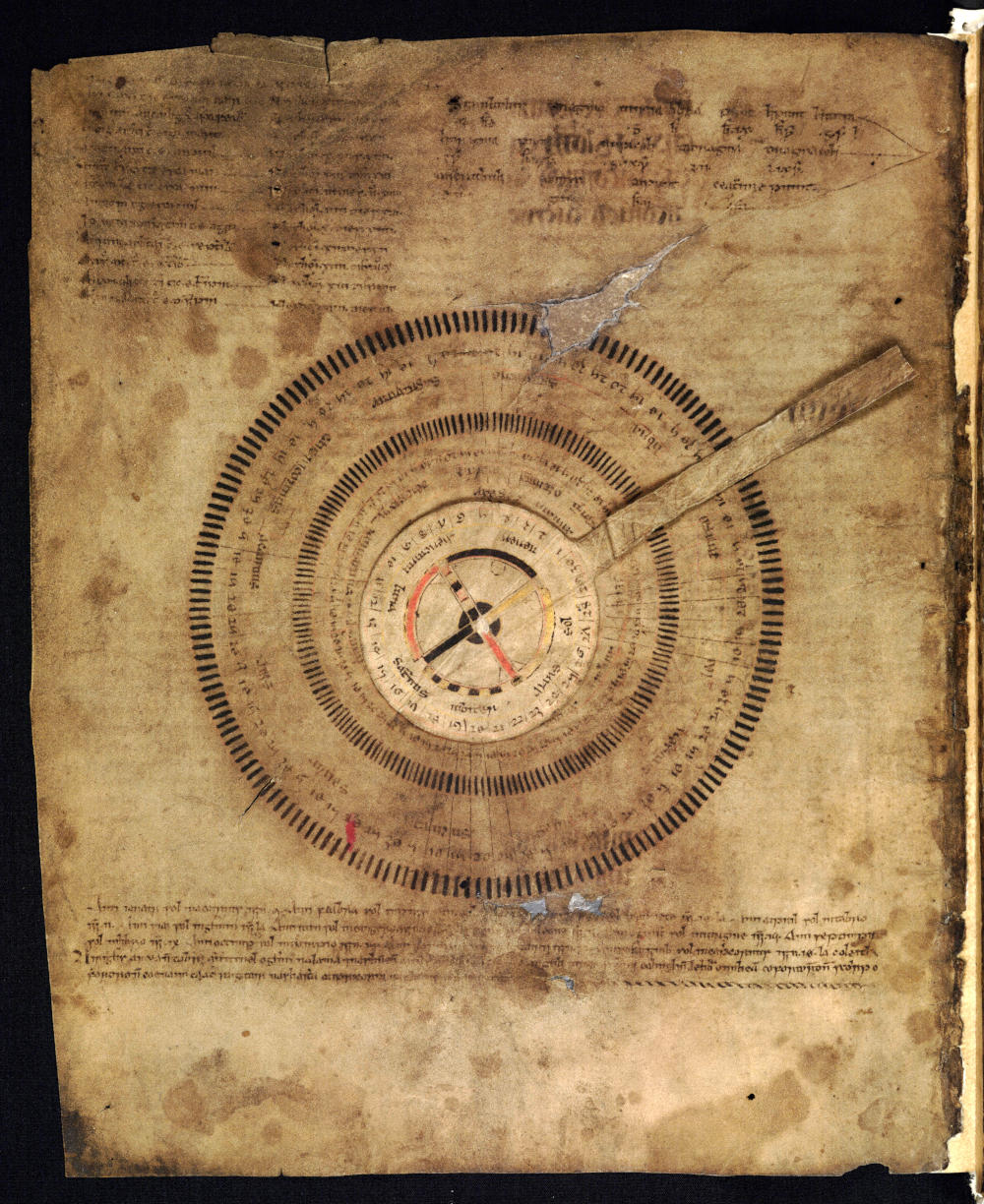

The perennial quest to understand the concepts of Time and Time-Reckoning challenged the great scholars of contemporary Europe. The task of calculating when Easter was to occur was a massively complex problem presented by the moon, tide and earth rotation. As early as the 7th century the Irish had become the leading experts on what was then termed computistics.

Manuscripts

One of Ireland’s greatest achievements and our most valuable treasures

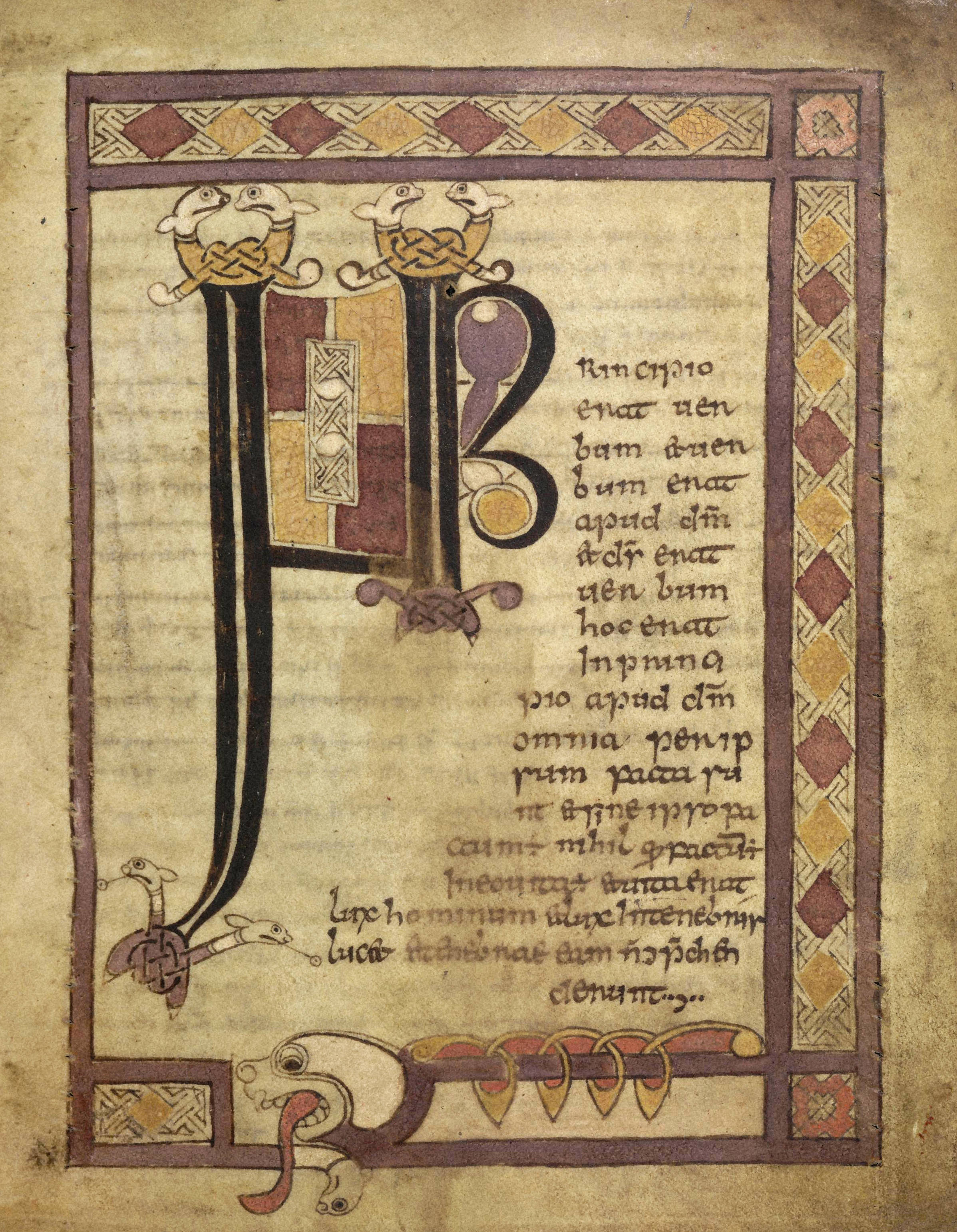

These manuscripts were written by highly educated scholars in centres such as Clonmacnoise and Monasterboice at a time when intellectual endeavour was highly regarded and pursued in Ireland and its teachers prized and much sought after in the royal courts of Europe.

Many of the manuscripts written at this time would have had a religious focus, as did many of the artworks produced in the same Irish centres of learning. To such centres we owe works such as the Book of Kells, the Durrow Gospels, the Ardagh Chalice and many of the other works of art for which Ireland is famous.

ISOS

Irish Script on Screen was established in 1999 by the School of Celtic Studies in the Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies. It was one of the first specialist manuscript-digitisation projects established in Ireland, and to date it is one of the longest-running in Europe. Gaelic Manuscripts are to be found throughout the world, in Libraries and in private collections. For the most part, they have found their way to large institutions throughout Ireland, Scotland, England and Wales. There are roughly five thousand surviving manuscripts that we currently know of. They range in date from the 6th to the 19th century.

Through ISOS scholars can now access all existing manuscripts relevant to their research. Bringing all the manuscripts together physically is not possible, however this can be achieved now virtually. This open platform allows Ireland’s unique manuscript heritage to be viewed and studied for the first time by the general public.

One of the key factors in the success of ISOS, is the high quality attained in the image capture itself. Images are digitized at a resolution of at least 600dpi with each pixel being 24 bit colour.

ISOS continues to be a very successful project. Its growth has been greatly facilitated by the development of institutional partnership agreements with all the major repositories of Irish manuscripts in Ireland, including the National Library of Ireland, the Royal Irish Academy, and Trinity College Dublin. It also has developed internationally with the likes of The National Library of Scotland, The State Library of Victoria, KBR the Royal Library of Belgium and The British Library coming on board. Collaborations to date reach some 28 different institutions, here and abroad.

There are now over 425 manuscripts on ISOS, upwards of 80,000 large-resolution images. All images are free of charge. ISOS provides a powerful tool to progress the study of Irish palaeography, to further manuscript studies and open the exploration of Celtic culture to many future generations to come.